There are not many times in my day-to-day life when I have the opportunity to just sit and be with my thoughts any more, but sitting in the darkness in the Redcliffe Caves in Bristol, waiting for the audience to emerge from what had become known to us as the ‘disappearing section’ of our piece for caves/underground spaces, Beneath Our Feet, I became aware again of that point in the life of any piece where it feels like it has grown into something separate from the making process, separate from me - something with a life of its own.

With the caves work in particular, this is the point at which the piece stops being something purely informative about the history of the site and becomes much more about the feeling of the extraordinary places to which we’ve had access over the past year, the memories of the ways in which those places have been encountered by hundreds, thousands, millions of people before us, and each individual audience member’s awareness of their own body in that unique environment.

“Reminded me that my lifespan is minute compared to natural landscape.” (audience member, Stump Cross Caverns)

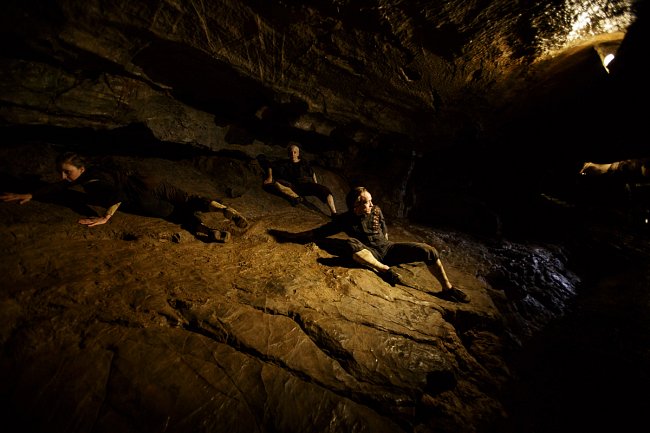

Working underground, the process of struggling to find the right way of telling the story of each site and then the gradual process of getting a little bit closer to doing so is very physical in itself. When first entering each cave or underground space with the team, there’s definitely a feeling of uneasiness, uncertainty, a burden (and not only because I’m carrying everyone’s valuables in my rucksack as we’ve travelled so far from our ‘green room’ space). I find myself adopting huddled shapes in dark corners, leaning awkwardly or hitting my head repeatedly as I try to get accustomed to the particular landscape. Then as the show settles in and we’ve performed it a few times I start to ease in, to find the spaces where it’s possible to stretch out and enjoy noticing things that I haven’t noticed before – different perspectives, and the pleasure of being in on a secret about something that is about to happen or being momentarily on my own in a place where I’m not supposed to be as the audience moves on to the next chamber, leaving me behind.

Over the past 6 years of working site-adaptively in response to heritage sites of all kinds, we’ve learnt a lot about the process of trying to find a way of feeling ‘at home’ in an unfamiliar place, as a way of trying to tell the story of each site, or more exactly of allowing the site to speak for itself.

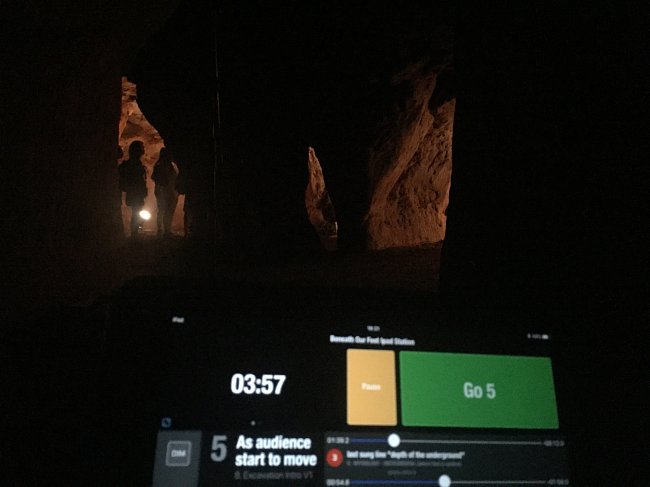

Just to give a bit of background, Beneath Our Feet is a promenade work for 3 dancers (Henry Curtis, Megan Griffiths and Lucy Starkey) and musician Lou Vilstrup. It has writing by Anna Selby, music by Max Perryment and Lou, design by Sarah Dicks and is produced by Kate McStraw and production-managed by Ellen Booth. It is made up of up to 10 sections and is usually about 45-50 minutes long. I say usually, because we never perform it in the same way in any 2 underground sites. To adapt it we can move the sections about, take sections out, add in new text and movement and respond to the particular features of each space for example. This draws on the model of site adaptive work we use for The Imagination Museum, and although it can be time-intensive we have found it to be effective because it enables us to create something unique to each site rather than trying to recreate something that doesn’t feel connected.

“I enjoyed being led through the caves and seeing how the movements were adapted to the environment – and how it was made specific to this cave” (audience member, Stump Cross Caverns)

Nowhere has this site-adaptive process been more challenging than underground. However, in spite of the particular challenges of the Dancing in Caves project – the unsteady floors, the darkness, the cold, the water, the mud, the challenges around accessing sites, the need to get kit in and out every day, sometimes up/down countless steps, to get the battery packs on charge, the mannequins to move and remember where to put back (all accomplished bravely by our Production Manager Ellen Booth, and also by Nic Prior and Dean Sudron along the way) – as a team we have certainly become accustomed to the process of finding a way of being ‘at home’ in what often, at first, seems to be a pretty inhospitable environment. Even Stump Cross Caverns, our most complicated site of the 2018 tour – 65 steps directly down and then most of the route through the caverns bent double with a hard hat (because you definitely do hit your head on multiple occasions), sometimes wading through water – seemed gradually to become more hospitable, the dancers able to navigate it and the audience more effortlessly.

“Beautiful, I really enjoyed it. The commitment to such full-on physical movement was surprising and impressive. I felt a strong connection with the performers.”

“The ease with which the dancers moved around the cave - so fluid.”

“Interaction with audience - very gently done and graceful”

“Magical performance in mysterious surroundings. Combination soft smoothness and brutality”

(audience feedback from Stump Cross Caverns)

Here are just a few of the things we've learnt while trying to allow each site to speak for itself:

- A site visit in advance is helpful for pre-planning, building trust with the team at the venue, starting to reorder sections, preparing a draft script, but nothing can replace the experience of actually coming together on-site. In practice, all of the challenges and solutions to those challenges present themselves more clearly. In order to make the best work possible we have to allow the cave to tell us where things need to go, and this comes about through trial and error.

- In the best situations there isn’t too much of a linear pathway through the site, there are options for going in different directions, doubling back, seeing the cave from a different perspective, for the dancers to go off the beaten track (even if the public have to keep to paths). This means we can do surprising things. At a site like Redcliffe, which isn’t usually open to the public, this is much easier, as the ‘well-trodden path’ hasn’t been decided upon.

- We work with the site team to make sure that everything we’re doing is in keeping with the conservation needs of the space, and Tara Beacroft at Kents Cavern has been particularly helpful in talking through the kinds of things we need to be aware of to ensure that our performance doesn’t have a negative impact on the site. Sometimes audiences are a bit surprised at how much we interact with the site, but everything we do is with permission from the owners/custodians of the space – the limitations they may put on our use of the space don’t have to be limiting, they just make us more considerate of our approach. We want to challenge each space’s potential but we do want to be respectful and not to leave any mark behind.

- We have been made acutely aware during this tour of Beneath Our Feet of the impact of feeling supported fully by the team managing each space. At our partner sites on private land (owned by someone often living in a house next door) or passed down through generations of a family, we have found that the team can be more deeply invested in the adaptation process, and are often more willing (and able) to allow us time and access necessary to make the best work possible. This definitely has a positive impact on the quality of our experience, which also translates into the audience’s experience of the piece.

- The infrastructure already in place around a venue is so important (or, where there isn’t any, trying to draw together that infrastructure in collaboration with other local arts and heritage partners). This includes all of the things that make unusual sites accessible – whether there’s a visitor’s centre, café, toilets on-site, parking etc – as well as the capacity to raise awareness about the event and a connection with the local community, perhaps a relationship with local schools to which we can offer workshops. By infrastructure I also mean the staff or the temporary stewards at a site like Redcliffe which isn’t permanently open to the public. The attitude of the people at the venue towards our project is essential, because those are the people who are the potential audience member’s first point of contact with the work. The care they take to learn and speak about the piece (we invite them to come, and to bring friends and family if they wish, to a preview performance during the rehearsal period) is part of the audience’s overall experience. One audience member at Stump Cross Caverns talked about the “Excellent hospitality” they had experienced, which I think points to this all-encompassing feeling of being taken care of, by the staff on-site and also the performers.

- As the tour has gone on, the expertise of the performers has developed quickly in response to multiple sites, and we learn more every time we do a new adaptation. However, we also have to be mindful about clearing the slate each time we begin again, rather than trying to recreate a previous version. We learnt that early on, when at Cheddar Gorge and desperately trying to hang on to the black-out/sense of an ending that we had achieved at Kents Cavern. The best thing we did (although it was hard to do, and I only realised it was necessary after the first couple of performances had already happened!) was to let it go, and to find the new way we needed to achieve a feeling of closure in a different site.

- Similarly we’ve harvested a vast amount of peculiar knowledge about managing all the technical elements of the work invisibly, with limited team and kit: small, seemingly insignificant things like knowing that if you light the taper candles at least once first before the audience use them, they will light more quickly during the performance, contributing to that invisible flow of things.

- I think we’ve learnt more during this tour about what it means to make the work specific to a place, without being beholden to its history. This is difficult/challenging for some of our audience members, who say in their feedback that they wish we’d mentioned this or that particular historical detail, but that isn’t really what we want to focus on with this project. We do research each site thoroughly, also interviewing local experts, and our understanding of the history of each place absolutely informs the adaptation. However, we try to find the balance between some historical detail and a more evocative sensory exploration of the space. We have tried adding more historical context to the piece, but it sits heavily within it. If we keep things more evocative, more atmospheric, we can allow space for the very personal experience of being underground in the moment, as well as recalling what has happened in the past. We would love it if by the end of the work each individual feels like they’ve landed more securely on their feet, as well as knowing more about the cave/underground space in an instinctive way, because this is what we can do/offer that is different to a more standard cave tour.

“It's fascinating how caves can be transformed, how sound and light carries and how both eyes and ears can play tricks on you - something you never really appreciate on a standard 'tour' of the underground, hence the 'magic' of the place can often remain unappreciated by the modern visitor.” (Miles Russell, Senior Lecturer in Prehistoric and Roman Archaeology, Department of Archaeology, Anthropology and Forensic Science, Bournemouth University)

All of these things are common sense really, but this bank of knowledge we’ve built up has proven invaluable, particularly in the most challenging sites.

An unsettling experience

Sharing a drink recently with some of the team, above ground and safe, we laughed about some of the unusual things that had happened during rehearsals underground. Bats circling over our heads, particularly liking the first track of Max Perryment's soundscore; lights cutting out at crucial points in rehearsal leaving us plunged in darkness and trying to stay calm; a ‘visitor’ tipping out one of our boxes of tapers overnight, smashing a couple of candle votives and slicing cleanly through one of our cables; windows banging and the disconcerting rumbling of trains heard from underneath the earth. At the time of each of these I have to say, with even the most rational perspective, I was pretty unsettled.

There’s something so affecting about making a journey underground, it makes you question things you thought you were certain of, reconsider your boundaries, the edges of things. I think that’s why we have had such beautiful feedback from people, who have described feeling moved:

“I teared up when entering the caves and hearing Lou sing - such moving space and sound.”

"Evocative, powerful and deeply affecting"

“Surprised by how emotional I found it.”

“The level of emotion surprised me.”

“I loved it - parts made me feel very emotional”

It’s to do with releasing or underscoring the inherent capacity of the underground to make people connect with themselves, to question what they know or think they know. It’s de-stabilising, but there is also potential here to feel more deeply connected with the earth and with yourself (and I don't quite know what this is about, but experience now suggests that there's something in it).

This is not to say it isn’t hard work (on-site but also on paper, trying to raise funds, persuade people, engage people) and the work wouldn’t be possible without sheer tenacity and willingness of an utterly brilliant team. Everyone has to be so on board with it for the project to happen, and no request is too great for Ellen, Henry, Megan, Lucy, Lou and Kate. It feels like we all share fully in the commitment to making/finding the best possible version of the work in every site. We’re all invested in it, we all take care of it.

And that includes my family, including Ben who’s now 10 months, who has possibly seen more of the underground than any other baby, and Emily who’s 3, and I think really believes that directing dance performances in caves is my full-time job. My family's patience and understanding has also been essential to making the best work possible, and when people say lovely things about their experience of the piece this is really rewarding, and feels like a huge group effort has been worth it.

It also isn’t possible without financial support, especially because we’re often working in remote places, with small capacity for audiences, with venues that haven’t worked in this way before, and we are hugely thankful to the Arts Council for their ongoing support of our work in heritage sites, as well as to those who funded us through Crowdfunding for the first time, supported us by paying for a ticket and attending or providing us with fees to share our work and the many individuals and organisations who offer in kind support, including everyone who helps us to raise awareness about the project.

It feels like this post began as a reflection on a making process and ended up being a love letter to the marvelous people with whom I’ve collaborated over the past year, which is right I think. It’s all part of the same thing. I think it can be easy to distance yourself from the living, breathing human process of creating something when you attend a performance, but with the caves project, the visceral sensation of moving underground like moving back in time, and the intimacy of the experience and a brief period of time when we’re all in it together, there’s somehow no getting away from it.